Purcell Report: How Courts And Defenders of Gerrymandering Misused an Obscure Rule to Disenfranchise 2.5 Million People

Purcell has been weaponized against civil rights to enable gerrymandering.

- Purcell v. Gonzalez established a practical concept that federal courts should avoid adjusting election rules too close to an election to prevent voter confusion—but it is now misused as an arbitrary bar against civil rights enforcement and voter relief. Courts tend to apply the concept earliest in redistricting cases, and forced over 2.49 million people to vote in districts already found to likely violate federal law in 2022 alone.

- Empirical research indicates a decision issued six months before the general election is only 3.4 percentage points less likely to apply Purcell than one issued three months before. This means that, notwithstanding Purcell’s focus on imminence, courts do not use the concept to avoid changes closer to elections, but instead use Purcell to avoid protecting voters no matter how far away the election is.

- Redistricting cases apply Purcell very unevenly across time relative to other election law applications of Purcell, such as ballot initiative cases.

- Historically, courts have applied Purcell most frequently in states with heavily gerrymandered legislatures, including Georgia, North Carolina, Ohio, Texas, and Wisconsin—enabling skewed legislatures to pass last-minute changes to keep their unearned power.

- Courts are considering and applying Purcell much more since 2016, and delaying implementation of new, legal maps by giving states longer to implement maps than in the early 1980s—despite significant increases in map-drawing technology.

- There are state and federal policy solutions that can prevent bad actors from improperly invoking this concept to limit voters’ access.

Many election observers talk about the “horse race” in the run-up to elections. But a more treacherous race between legislatures and courts is also underway behind the scenes, as new election administration policies are passed, then challenged in court.

In an era where election rules are politicized and conservative forces have weaponized false claims of voter fraud to restrict access to the ballot under the guise of election integrity, voting rights litigation serves as an important check on restrictive, discriminatory legislation. This is especially true in gerrymandered states, where unresponsive legislatures—intent on holding onto unearned power—pass one restriction after another, leaving the courts as the only avenue for voters to ensure they can participate in free and fair elections.

Unfortunately, the law has shifted in recent years, increasingly putting time on the side of state defendants—those who are passing new, burdensome voting laws and biased maps—at the expense of voters. As new data shows, what started as a practical legal solution has been transformed into a manipulative move that hurts voters, letting state defendants run out the clock to their advantage.

Time has always been critical in civil rights litigation.

Congress has long recognized that state governments intent on holding power may change the rules at the last minute to benefit themselves and to disadvantage or discriminate against voters. One of the anchors of the Voting Rights Act—the most effective civil rights statute in history—was Section 5’s preclearance regime, which required states with a history of discrimination to get approval (or preclearance) from the U.S. Attorney General or a federal court before making any changes to election administration. To ensure that these states did not continue to enact laws that spread voter suppression, any election changes were reviewed by a court before implementation, as opposed to allowing the policy to be implemented before it could be challenged. This put time on the side of voters, forcing states to justify any restrictive changes and pause implementation if they were not sufficiently justified, as well as limiting states from making last-minute attempts to upend election processes.

Under preclearance, states were given limited time to make changes. When it came to redistricting, maps were often significantly harder to draw given the limits of technology. Nonetheless, the Department of Justice under both Republican and Democratic presidents refused to preclear maps from states throughout the South and gave states short, but evidently adequate, time to redraw maps. For instance, in Alabama in 1982, the Department of Justice under President Ronald Reagan refused to preclear the state legislative maps proposed by the legislature less than four months before the state’s primary election and gave the legislature another chance to pass a new plan.1 In Texas in 1991, the Department of Justice under President George H.W. Bush refused to preclear Texas’s state house map just three weeks before the candidate filing deadline, and less than four months before the primary election, stating “We believe that sufficient time remains for the state to make the necessary adjustments to the submitted plan and to obtain Section 5 preclearance for the plan so that the election may proceed on schedule under a plan that meets the requirements of federal law.”2

The conservative movement has long sought to put the passage of time on their side. The 2013 Shelby County decision by the U.S. Supreme Court nullified the preclearance requirement and within days, states passed restrictive provisions.3 As a result, instead of being able to stop discriminatory legislation before being put into practice, litigators must now rush to court and file emergency motions for preliminary injunction, hurrying to stop provisions that could hurt voters’ ability to exercise their rights.

Soon, the conservative movement went even further, aiming directly at legal claims that sought emergency relief after discriminatory measures were passed. Purcell postponements have been weaponized by legislators, conservative legal advocates, and sympathetic courts to delay plaintiffs’ ability to challenge legislation and receive timely relief, allowing elections to proceed under policies that courts have already determined to be discriminatory. Legislators are aware of this and may intentionally wait until the last possible minute to pass restrictive bills, knowing that before any court can hold them accountable, they may be able to sneak in a “freebie” election with their new discriminatory rule, restriction, or illegal map in place. Voting rights advocates are forced to respond immediately to all new bills in order to try to lift burdensome laws and maps before voters’ rights are irreversibly lost.

While Shelby County snatched time from voters in one dramatic swipe, the increasing reliance on Purcell over the last two decades has been a silent—but no less terrifying—drain of sand from the hourglass.

Purcell began as a practical rule—but is now an inconsistently applied bar on civil rights relief.

Purcell arose from a short, practical ruling that the Supreme Court decided without the benefit of oral argument. In 2006, in an emergency stay application on the shadow docket4, the Court issued what—at the time—was a pragmatic ruling tied to timing, with an election less than three weeks away. In Purcell v. Gonzalez, the Court reversed the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, which had paused the implementation of Arizona Proposition 200, a measure requiring voters to show proof of citizenship to register to vote and cast a ballot on election day.5

The Court noted several factors in its short, unsigned decision. It discussed how the state’s interest in new election rules ostensibly to ensure the integrity of the election could be in tension with voters’ fundamental right to vote. The Court emphasized that “Court orders affecting elections, especially conflicting orders, can themselves result in voter confusion and consequent incentive to remain away from the polls. As an election draws closer, that risk will increase.”6 Without the benefit of a trial in the lower court, and on an emergency basis on appeal, the Court issued what it implied was a practical ruling due to the “impending election [and] necessity for clear guidance.”7

Nonetheless, what started as a practical solution in an emergency stay application has broadened significantly into a widespread application of unnecessary Purcell postponements, based increasingly loosely on “the idea that courts should not issue orders which change election rules in the period just before the election.”8 While at the time, the Purcell decision discussed how federal courts should weigh many factors before altering the status quo in election cases, the case has since been cited by defendants to claim that any remedies cannot be applied “close” to an election.

In 2022 alone, Purcell’s application forced over 2.49 million people to vote in districts invalidated by courts.

Purcell’s application in redistricting cases has been especially devastating.

In the 2022 elections alone, five maps invalidated by controlling opinions were not fixed because courts refused to change maps under Purcell. In Alabama, a three-judge federal district court panel in the Milligan case found in January 2022 that the state’s newly enacted congressional map likely violated Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, and granted a preliminary injunction against the map being used in any election.9 However, the U.S. Supreme Court granted an emergency application for a stay filed by the state and docketed the case for oral argument in the October 2022 court term.10 In a concurrence, Justice Kavanaugh emphasized Purcell, even though primary elections in the state were over 100 days away, in late May.11

Following the U.S. Supreme Court’s grant of a stay in Milligan, several other maps were found to likely violate Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, but relief was also stayed on Purcell grounds. In Louisiana, after a lower court enjoined that state’s congressional map, the U.S. Supreme Court paused the case pending the outcome of Milligan, again delaying relief against a map found by a controlling opinion to likely violate the Voting Rights Act until after the 2022 elections.12 Similarly, in Georgia, a federal district court found that the state’s congressional, state senate, and state house maps likely violated the Voting Rights Act, but refused to block the maps prior to the 2022 election, noting the Milligan stay.13

After the 2022 elections, the U.S. Supreme Court issued Allen v. Milligan, affirming the lower court’s ruling that the map likely violated Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act.14 After a full trial, the trial court determined in 2025 that the map did indeed violate the VRA.15 The Georgia decision was also affirmed following a full trial as well.16 And on remand in the Louisiana case, after the Fifth Circuit affirmed the district court’s factual findings, the 2024 Louisiana legislature subsequently redrew the map to ensure compliance with VRA Section 2.17 Thus, the use of unnecessary Purcell postponements ultimately delayed relief that courts considering the issue had determined voters were entitled to. Across these three states alone, over 2.49 million people were denied equal representation for two years and forced to vote under illegal maps because of Purcell.18

“Across these three states alone, over 2.49 million people were denied equal representation for two years and forced to vote under illegal maps because of Purcell.”

This estimate includes voters in Alabama’s second congressional district, Georgia’s sixth congressional district, and Louisiana’s sixth congressional district, as well as voters in Georgia Senate Districts 17 and 28 or House Districts 64, 74, and 117 who were not otherwise in another affected Georgia district. All of the aforementioned districts were on maps found by controlling federal court opinions to be likely violations of the Voting Rights Act and were subsequently changed following the 2022 elections. The estimate of 2,490,953 people is based on data from the 2020 Census.

Worse still, the U.S. Supreme Court did insert itself in Wisconsin’s redistricting process to order a new map in 2022, rather than letting the map the state adopted stand, even after it issued the stay in Alabama.19 There, a state court had adopted new legislative maps through a court

process after the state’s legislature and governor failed to agree on maps. But, after the state’s highest court adopted legislative maps, a group of conservative activists appealed the adoption of the new maps on race-based grounds to the U.S. Supreme Court. The Court, in an emergency posture, reversed the state supreme court, even though no racial gerrymandering claims had been made in the lower court and no party had brought a racial gerrymandering case. Across redistricting challenges occurring in the same year, Purcell postponements were

applied inconsistently—to the detriment of over 2.49 million voters.

Ahead of the 2024 elections, there was only one congressional redistricting case where the U.S. Supreme Court issued a stay delaying relief until after the election. That decision, arising from Louisiana, allowed a new map that protected Black voters to proceed against a new legal challenge. Nonetheless, the case remains the exception that proves the rule: Justice Jackson—a justice who has previously sided with voters in similar voting rights cases—dissented from the high court’s order. In her dissent, which was joined by Justices Sotomayor and Kagan, she specifically noted the inconsistency in Purcell’s apparent application, stating that “There is little risk of voter confusion from a new map being imposed this far out from the November election. In fact, we have often denied stays of redistricting orders issued as close or closer to an election.”20 The Court’s order came 174 days—nearly six months—before the state’s primary election, despite the fact that all parties had acknowledged that the state legislature had taken only several days to draw the map in question.

The 2024 case is particularly striking for its timing. Before Shelby County, if there was no compliant map in place, a court would draw an interim one. Now, when no compliant map is in place, the state benefits by letting its challenged map remain—meaning the state has every incentive to say it needs more time to implement a map. And yet, even when states now have incentives to say they need more time and should thus be scrutinized more closely, courts have instead given them additional time. In an era when maps can be drawn in minutes with freely available online tools, the U.S. Supreme Court gave Louisiana more than a month longer than the H.W. Bush or Reagan Justice Departments had given Alabama or Texas—even though those decisions came down before widespread personal computers and the internet, respectively—in which maps took much more time to draw.

Purcell’s effects can be—and for the first time, have been—quantified.

As a legal concept, Purcell’s focus on the timing of elections makes its impact measurable. It is straightforward to calculate the time between when a decision is issued and the election, and analysis of those timelines can provide voting rights advocates with the tools to push back against inappropriate expansions of the concept.

This report produces a comprehensive empirical analysis of all applications of Purcell in the nation.21 As the data shows, what started as a practical guideline has been deliberately mutated into an inconsistently applied “get-out-of-jail-free card” for state defendants in voting rights cases.22

However, as the data shows and courts23 and commentators alike24 have pointed out, not all hope is lost. Courts do not apply Purcell uniformly, but existing doctrines can be used to right-size the concept back to practicality. Moreover, states can—and should—protect voters through legislation that prevents the Purcell postponements from being invoked for partisan gain and require election officials to establish final deadlines for key steps in election administration well in advance, limiting opportunities for gamesmanship with deadlines.

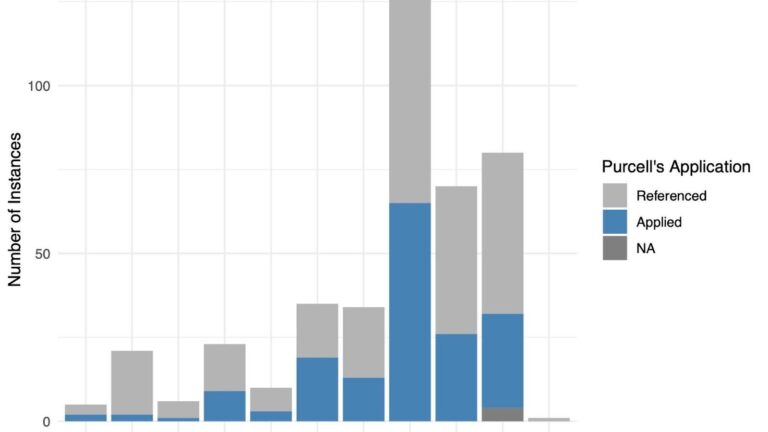

As new data shows, Purcell’s use has greatly increased.

Despite its short ruling and case-specific practical reasoning, citations to and applications of the unsigned 2006 Purcell order have ballooned in recent years, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1Rate of Cases Citing Purcell by Election Cycle (2006-2024)

This stacked bar graph details the rate of judicial opinions citing and applying Purcell from 2006 through 2024, by election cycle.

Taking both presidential and non-presidential cycles separately, Purcell citations have increased year-over-year every cycle since its inception, apart from an outsize spike in 2020. Its usage has also generally been higher in presidential years and cases from the 2020 election cycle alone account for nearly 40% of all Purcell applications.25

Purcell is also being increasingly applied even in non-presidential years. In 2022, a full 29 cases applied Purcell from a total of 84 cases that mentioned it. That is more than the same numbers for 2018, where 13 cases applied it from a total of 36 that discussed it.

Amidst this vast increase in usage, Purcell is not uniformly applied, leading to different outcomes for voters.

I. The legal concept behind Purcell implies that it should be applied more often when a voting deadline approaches.

Justice Kavanaugh, in a concurrence accompanying the Court’s stay of relief in Allen v. Milligan, claimed that Purcell reflects a “bedrock tenet of election law,” that with elections “close at hand,” the rules must be set out clearly, because otherwise “[l]ate judicial tinkering with election laws can lead to disruption and to unanticipated and unfair consequences.”26 He acknowledged, however, in a footnote that “[h]ow close to an election is too close may depend in part on the nature of the election law at issue.”27 As discussed above, the Court ultimately affirmed on the merits, meaning the pause itself only delayed relief for voters and had no tangible benefit.

While Justice Kavanaugh’s full-throated endorsement of the concept acknowledged that different types of election law cases may qualify for delays under Purcell at different times, his premise is empirically testable: are cases applying Purcell occurring close to elections on average? Even if there are different types of claims at issue, to faithfully follow his framework would require cases, on average, to apply Purcell more often as the election gets closer. In other words, the idea that courts should limit their involvement right before an election suggests that Purcell should be applied more frequently as voting deadlines loom closer.

However, the concept does not appear to be uniformly considered by courts. Examples abound: a three-judge panel in the Southern District of Ohio applied Purcell over 200 days before the court’s stated election deadline of interest, whereas a judge in the Southern District of New York distinguished the Supreme Court’s concerns in Purcell from that in the case before it and resisted application of the concept eight days before the election.28 Scholars and advocates have amply criticized Purcell for its undefined nature.

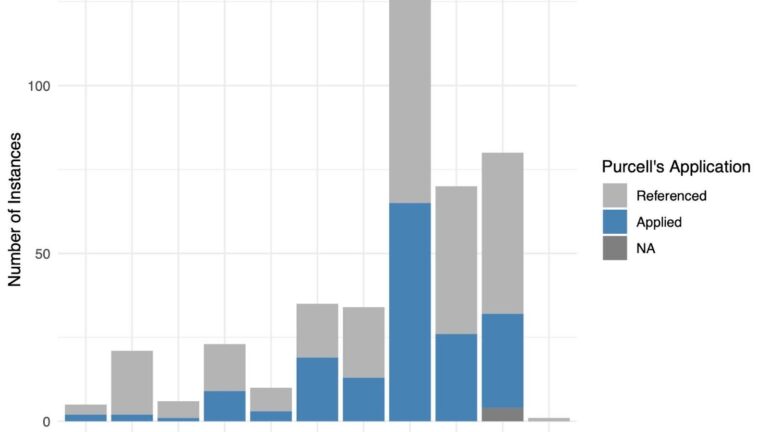

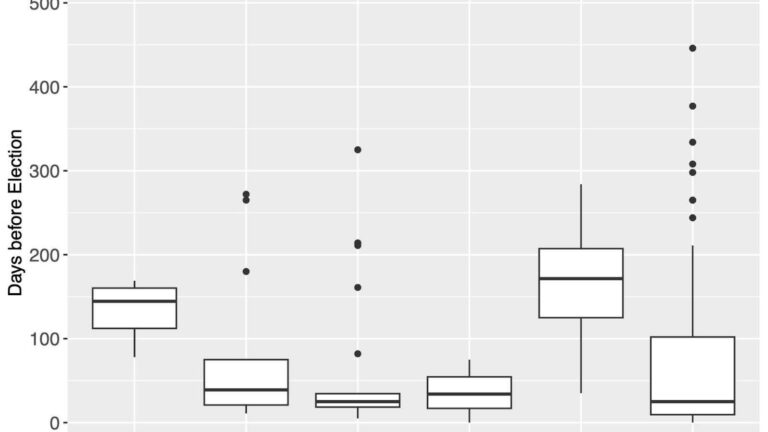

Figure 2Timeliness of Purcell Application by Challenge Basis

Across all years, courts have applied Purcell at very different times before the general election. Each bar represents the number of cases that applied Purcell, stacked together in groupings of 30-day periods, thus roughly corresponding to the months leading up to a general election, with the left being closest to the election and the right being the furthest from the election. The graph shows how variable applications of Purcell can be across time: for instance, Ballot Initiative challenges generally apply Purcell in a narrow window of time centered around 144.5 days before the election, while Voting Procedures cases apply Purcell at moderate rates throughout 300-odd days before the election. Application to Redistricting challenges has been extremely variable.

Across all years, courts have applied Purcell at very different times before the general election. Each bar represents the number of cases that applied Purcell, stacked together in groupings of 30-day periods, thus roughly corresponding to the months leading up to a general election, with the left being closest to the election and the right being the furthest from the election. The graph shows how variable applications of Purcell can be across time: for instance, Ballot Initiative challenges generally apply Purcell in a narrow window of time centered around 144.5 days before the election, while Voting Procedures cases apply Purcell at moderate rates throughout 300-odd days before the election. Application to Redistricting challenges has been extremely variable.29

II. Empirical evidence demonstrates that notwithstanding Purcell‘s focus on election imminence, courts do not use the concept to avoid last-minute changes, but instead use Purcell to avoid protecting voters no matter how far away the election is.

Purcell is not applied evenly in a way that voters in similar cases have similar time to protect their rights and challenge new barriers to voting.

Among every case applying Purcell from 2006 to 2024, decisions were issued a median of 35 days before the general election. And yet, comparing the date of the opinion being issued across time, the number of days before an election had only a small effect on the likelihood of that case applying Purcell. Regressing time across whether Purcell applied, among all 411 federal cases analyzed, the coefficient associated with the number of days the opinion is issued before the general election is -0.0007031, meaning that the time between the court issuing a decision and the election had a relatively inconsequential effect on whether Purcell was applied. The substantive effect of the number of days prior to a general election and the invoking of Purcell is fairly small compared to what the legal doctrine implies it should be. This is especially noticeable when we consider a time period of six months before an election and three months before an election, both of which are significant time periods. When considering the difference between six months prior to the election and three months prior to the election, Purcell is invoked only about 3.4 percentage points more frequently in election law cases issued 90 days before Election Day compared to 180 days before Election Day.30

While deadlines before elections are set far ahead of time, states and courts can shift the goalposts and identify different potential deadlines as the relevant date. For instance, depending on the circumstances of the challenge, the relevant deadline could be the candidate filing deadline, the ballot printing deadline, or the election itself. Courts have discretion to determine which deadline is relevant, and states may use this to their advantage, insisting that an early preliminary deadline is set in stone, while voters and advocates are left to argue that preliminary process-based dates can be adjusted to ensure a fair election. No matter which deadline the court determines is relevant for the case, comparing Purcell rates to the number of days before the general election allows for comparisons across cases and time, and is therefore the focus of this analysis. That being said, comparing whether Purcell applied to the court’s own stated deadline yields similar results.

Looking within specific types of voting rights cases, each challenge type includes at least one case that applied Purcell more than 150 days before the general election.

Moreover, in cases concerning voting procedures, the middle 50% of cases that applied Purcell measured by days before an election range from a week and a half before the election (11 days) to nearly four months beforehand (110 days). This indicates that in cases challenging voting procedures, judges seem to be interpreting the same concept, and the same type of issue, in vastly different ways.

Indeed, just as Justice Kavanaugh had feared, “judicial tinkering” has led to “unanticipated and unfair consequences.” But the tinkering—and consequences—are caused by misuses of Purcell, not protected by it.

Thus, with Purcell, the problem is fundamental. Across every case, despite its supposed focus on imminence, the amount of time before the election appears to have little to do with the decision to apply Purcell. While this result is striking, this fact alone does not explain why such wide variation in Purcell’s application occurs. Regardless, Purcell’s stated relationship between the time of the decision and the time of the election is not reflected empirically.

III. Purcell is generally applied earliest in redistricting cases.

While time does not appear to apply consistently to any Purcell case, Purcell is applied at slightly different times on average across different types of voting rights cases. This illustrates that courts may give themselves significant leeway to apply Purcell differently across different types of election cases.

Across all cases from 2006-2024, the median number of days Purcell has been applied is earliest in redistricting cases. As Figure 3 indicates, in redistricting cases Purcell is applied a median of about 174 days (six months) before the general election. This means that Purcell’s effects are felt a particularly long time before elections in redistricting cases. Given the frequency with which maps are being redrawn—Americans have not voted on the same Congressional map two election cycles in a row in a decade—Purcell is often a bar on relief.

Figure 3Median Timeliness of Purcell Application by Challenge Basis

This box-and-whisker plot indicates the spread of how many days before the general election Purcell was applied based on the type of election procedure being challenged. The median is represented by the line within each box, with 50% above and 50% below. The middle subset of cases, from 25 to 75% is represented within each box. Purcell is applied a median of 144.5 days before an election in cases involving ballot initiatives and a median of 174 days in cases involving redistricting, the furthest out for any type.

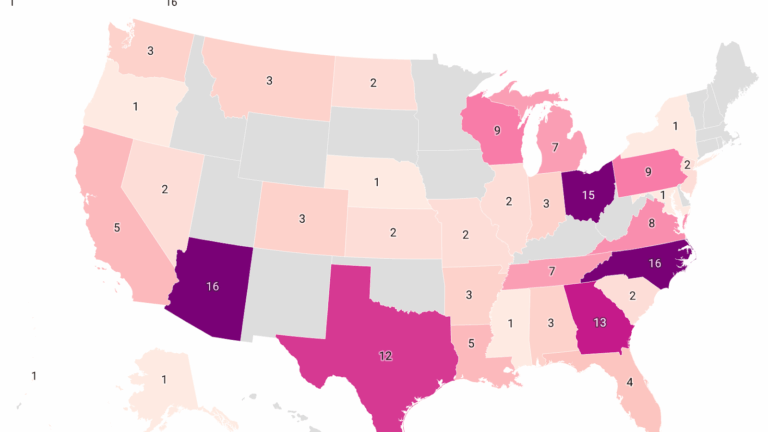

IV. Purcell has historically been applied most often in gerrymandered states.

Unsurprisingly, Purcell is most likely to be invoked in states where challenges are made ahead of highly competitive elections. Thus, it is not surprising that the concept has been invoked most often in traditional battleground states, where elections may be anticipated to be closest and where legislatures have the strongest incentives to change election rules, as such changes could affect election outcomes and are most likely to do so in close races.

Across the 2006-2024 data, courts have applied Purcell in cases across 34 U.S. states and territories. Among those, Arizona, Georgia, North Carolina, Ohio, Texas and Wisconsin—many of which have been key battleground states in the past 20 years—have seen the most cases where courts applied Purcell to hold off on granting relief to voters.

Figure 4Purcell Applied, Cases by State and Territory (2006-2024)

This map shows the rate of cases applying Purcell by state and territory from 2006 through 2024. Darker states have had the concept invoked more frequently.

But beyond living in battleground states, voters in Georgia, North Carolina, Ohio, Texas and Wisconsin have something else in common: They have endured some of the most heavily gerrymandered legislatures throughout the past twenty years. When these heavily gerrymandered legislatures create new barriers to voting that are challenged by civil rights groups in federal court, these same states have been most likely to have courts allow the provisions to remain in place and refuse relief to voters.

Because Purcell puts time on the side of defendants, savvy state actors may misuse it by delaying election changes until the last minute.

After the 2020 Census, the Georgia legislature passed new congressional and state legislative maps in 2021, but Governor Brian Kemp waited over a month to sign them, finally signing them just before New Year’s Eve, even though there was “never a doubt” that he would approve them.31 It was common knowledge at the time that he did so to delay challenges to the maps, in an attempt to allow the new maps to be used for at least one election even if they were later found illegal.

By waiting a month to sign the bills, Governor Kemp delayed the ability of voting rights groups to challenge the maps because of fears that a challenge to a map before the Governor approved it would not be legally “ripe” for such a challenge. By waiting, Governor Kemp took valuable time away from voters to challenge the anticipated violation of their rights.

Despite challenges to the maps being filed the very day they were signed, defendants ultimately invoked Purcell in the case, and relief was stayed until after the 2022 elections. Governor Kemp’s gamesmanship paid off — and Georgia voters paid the price.32

In 2025, as part of a nationwide push to enact additional gerrymanders, Missouri’s Governor Mike Kehoe similarly waited 16 days after the legislature passed a new congressional map to sign it into law, despite the fact that the map the legislature passed was the very map he had not only proposed, but also ordered the legislature into special session to pass.33 The challenges to the Missouri map are ongoing, but the 2026 election is fast-approaching. Taken together, Purcell enabled savvy state actors to use intentional delay tactics to improve their litigation chances, a dynamic that was extended by additional last-minute changes as part of the 2025 mid-decade gerrymandering crisis.

Now that Purcell’s damaging effects have been measured, policymakers must act.

State and federal governments can put a stop to Purcell’s inconsistent and atextual judicial meddling. The Supreme Court has not grounded the idea in any law or constitutional provision. It can thus be disclaimed by statute or mitigated by many other measures.

Some solutions may include:

The proposed legislation includes provisions that limit the ability of bad state actors to intentionally manipulate Purcell in their favor, by clarifying that “proximity of the action to an election shall not be a valid reason to deny . . . relief”34 to voters and requiring federal courts to appropriately weigh the “public’s interest in expanding access to the right to vote”35 in any such claims.

To prevent future power grabs by gerrymandered legislatures, state laws could limit the power of any state defendant to invoke Purcell without approval by bipartisan boards, or by ⅔ of the legislature.

- Legislation taking away certain powers to litigate for injunctive relief has been used before and upheld by state courts, though it may depend on state-by-state separation of powers concerns.36 State laws could mandate that Purcell not be invoked by state actors in litigation except in narrow circumstances.

- Moreover, Purcell can be stipulated out of lawsuits, as the U.S. Supreme Court emphasized in Rose v. Raffensperger.37 State laws could favor stipulations in such cases.

to prevent hurry up-and-wait tactics.38 Moreover, given that many states already have deadlines set by state law for elections, and for new maps to be passed every decade following the federal census, courts could set aside time to handle such predictable changes and challenges.

Meaning Purcell should only apply when judicial changes would decrease participation, not when it would increase or stay the same. Initially, Purcell sought to prevent voter confusion due to last-minute changes. A focus on increasing voter turnout would reaffirm Purcell‘s original mission.39 States, through statute or Opinions of the Attorney General, can define the concern with “voter confusion” described in Purcell as rooted in voter participation.

As states are required to draw new maps following each census, every election following the census is, by definition, not on a status-quo map. If Purcell is about preserving the status quo to avoid confusion, it does not make sense to apply when any solution will be a different map than the one used in the last election.

Primary Author: Jacob Carrel40

Footnotes:

- Letter from William Bradford Reynolds, Assistant Attorney General, Civil Rights Division, to Charles A. Craddick, Attorney General, State of Alabama (May 6, 1982) [https://perma.cc/AF5S-Z2ZV]; See Burton v. Hobbie, 543 F. Supp. 235, 236 (M.D. Ala. 1982) (noting primary election scheduled for September 7, 1982); It was not until the Department of Justice rejected the legislature’s proposed map again on June 8—only 91 days before the primary—that a court adopted an interim map. Id. at 237.

↩︎ - Letter from John R. Dunne, Assistant Attorney General, Civil Rights Division, to John Hannah, Jr. Secretary of State, State of Alabama (Nov. 12, 1991) [https://perma.cc/FC3J-KD67].

↩︎ - See Brennan Center for Justice, The Effects of Shelby County v. Holder (Aug. 6, 2018) [https://perma.cc/A43J-T4NM] (“Within 24 hours of the ruling, Texas announced that it would implement a strict photo ID law.”).

↩︎ - The “Shadow Docket” is an umbrella term for the U.S. Supreme Court’s orders and summary dispositions done outside of the Court’s normal process, which can still be precedential, despite that they are not subject to the “high standards of procedural regularity set by its merits cases”. See William Baude, Foreword: The Supreme Court’s Shadow Docket, 9 NYU J. L. & Liberty 1, 4-5 (2015) [https://perma.cc/WWE3-TF67]. See also Steve Vladeck, The Shadow Docket: How the Supreme Court uses Stealth Rulings to Amass Power and Undermine the Republic 199 (2023) (further connecting the Shadow Docket and the use of Purcell in redistricting cases).

↩︎ - 549 U.S. 1, 6 (2006).

↩︎ - Id. at 4-5.

↩︎ - Id. at 5.

↩︎ - Richard L. Hasen, Reining in the Purcell Principle, 43 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. 427 (2016) [https://perma.cc/59YH-7QXC].

↩︎ - Milligan v. Merrill, 582 F. Supp. 3d 924, 936 (N.D. Ala. 2022).

↩︎ - Merrill v. Milligan, 142 S. Ct. 879 (2022).

↩︎ - Id. at 882 (Kavanaugh, J., concurring in grant of stay). Alabama’s 2022 primary election occurred on May 24, 2022.

↩︎ - Ardoin v. Robinson, 142 S. Ct. 2892 (2022).

↩︎ - Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity Inc. v. Raffensperger, 587 F. Supp. 3d 1222, 1320 (N.D. Ga. 2022).

↩︎ - Allen v. Milligan, 599 U.S. 1, 42 (2023).

↩︎ - Caster v. Allen, No. 2:21-CV-1536-AMM, 2025 WL 1643532 (N.D. Ala. May 8, 2025).

↩︎ - Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity Inc. v. Raffensperger, 700 F. Supp. 3d 1136, 1380 (N.D. Ga. 2023).

↩︎ - Robinson v. Ardoin, 86 F.4th 574, 602 (5th Cir. 2023); S.B. 8, 2024 Extraordinary Session (Louisiana), R.S. 18:1276.1 (2024).

↩︎ - This estimate includes voters in Alabama’s second congressional district, Georgia’s sixth congressional district, and Louisiana’s sixth congressional district, as well as voters in Georgia Senate Districts 17 and 28 or House Districts 64, 74, and 117 who were not otherwise in another affected Georgia district. All of the aforementioned districts were on maps found by controlling federal court opinions to be likely violations of the Voting Rights Act and were subsequently changed following the 2022 elections. The estimate of 2,490,953 people is based on data from the 2020 Census.

↩︎ - Wis. Legislature v. Wis. Elections Comm’n, 595 U.S. 398, 406 (2022) (per curiam). However, the Alabama stay order was issued on February 7, 2022, 106 days before the state’s primary election was set to occur on May 24, 2022, and the Wisconsin order was issued on March 23, 2022, 139 days before the state’s primary election was set to occur on August 9, 2022. It is possible the Court felt the 33-day difference gave Wisconsin adequate time to adjust its maps in a way that Alabama did not, though the different posture of the Wisconsin case meant that unlike in Alabama, where remedial proceedings had begun and a special master had already been identified to adjust the one district at issue as soon as possible after February 8, the lower court in Wisconsin didn’t adopt new statewide maps for its upper and lower chambers until April 15, 2022, which was only 116 days before the primary election. ↩︎

- Robinson v. Callais, No. 23A994 (S. Ct., May 15, 2024), 601 U. S. ____ (2024) (Jackson, J., dissenting). ↩︎

- Every case citing Purcell from its inception in 2006 through 2024—411 cases in all—has been carefully coded by multiple independent legal coders on dozens of identifiers, including the type of law challenged, the time before the election, the judge, the plaintiffs’ claims, and more. For similar research that looks solely at U.S. Supreme Court’s orders, see Rachael Houston, Does Anybody Really Know What Time It Is?: How the US Supreme Court Defines “Time” Using the Purcell Principle, 23 Nev. L. J. 769 (2023) [https://perma.cc/QPG3-D84P].

↩︎ - Researchers interested in a full description of methods and the codebooks used should contact the authors.

↩︎ - See, e.g., Pierce v. N. Carolina State Bd. of Elections, 97 F.4th 194, 247 (4th Cir. 2024) (4th Cir 2024) (Gregory, C.J., dissenting) (“no precedential Supreme Court opinion has ever addressed Purcell’s proper scope. Left to decipher conflicting separate writings by individual justices, inconsistent lower court applications of the doctrine come as no surprise”); id. at 246–48 (“the Supreme Court’s admonition to the court of appeals to stay its hand is better understood as an instruction not to sacrifice the integrity of its judicial proceedings to the urgency of the moment. It is not a mandate that courts sit on their hands in the weeks before the election, when they still have time to engage in reasoned decision-making, solely because an election is impending. . . . Properly applied, the Purcell principle should be incorporated into a court’s consideration of the equitable preliminary injunction factors.”). ↩︎

- See, e.g., Nick Stephanopolous, Freeing Purcell from the Shadows, Take Care Blog (Sept. 27, 2020), https://perma.cc/H6QK-M43K (“courts shouldn’t assume that their interventions close to election day will be confusing or even disenfranchising. Instead, they should analyze whether this will be the case.”).

↩︎ - One potential reason for this relates to adjusted election procedures as a result of the pandemic, though further research may shed additional light. See also Wilfred Codrington, Purcell in Pandemic, 96 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 941 (2021) [https://perma.cc/S4RF-QB5Z].

↩︎ - Merrill v. Milligan, 142 S. Ct. 879, 881-82 (2022) (Kavanaugh, J., concurring in grant of stay).

↩︎ - Id. at 882 n.1.

↩︎ - Compare Gonidakis v. LaRose, 2022 WL 1175617 (S.D. Ohio, Apr. 20, 2022) with NAACP v. East Ramapo Central School District 464 F.Supp.3d 587 (2020).

↩︎ - Cases that apply Purcell after the election has already happened and cases that apply Purcell more than 365 days before the general election are not depicted. Cases coded as concerning Election Procedures had to do with items related to the election that were larger scale than voting, such as concerns over the election date or campaign finance regulations, or did not directly affect voters’ individual experiences, such as counting procedures. Cases coded as concerning Voting Procedures more directly affected how voters cast ballots, such as voter identification requirements or mail-in opportunities.

↩︎ - This effect size number as well as others presented in this paragraph are based on a regression model examining the statistical association between days before the general election and the invocation of Purcell. However, these small-magnitude effect results hold under many other statistical specifications. Additional statistical analyses using other deadlines all showed relatively small differences in the invocation of Purcell; as did additional analyses that considered a potential parabolic effect of the days before the general election and other deadlines. In short, no matter if days were included as a linear independent variable, as non-linear independent variables, or whether the days measured timing from the general, from the primary, or from the court’s own deadline of interest, the results show that there were very small substantive effects even with a statistically significant relationship between days before election/deadline and the invocation of Purcell. In short, the magnitude of the effect of days prior to the election is small even though statistically significant, leading us to conclude that time before election is not a substantively meaningful predictor of invocation of Purcell.

↩︎ - Mark Niesse and Maya T. Prabhu, Georgia redistricting signed into law and lawsuits quickly follow, Atlanta J. Const. (Dec. 30, 2021) [https://perma.cc/3HX3-QA3Z].

↩︎ - Prior to Shelby County, Georgia would have been covered by preclearance. The Department of Justice would have required the state to preclear its map before implementation, rather than to benefit from its own intentional delay. See generally Christian R. Grose, Congress in Black and White: Race and Representation in Washington and at Home (2011).

↩︎ - Complaint at *18–*21, Healey v. Missouri, Case No. 2516-CV31273 (Jackson Cty. Cir. Ct., Sept. 28, 2025) [https://perma.cc/9W5A-GMDB].

↩︎ - John R. Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act of 2023, H.R. 14, 118th Cong., 1st Session (Sept. 19, 2023), §11(b).

↩︎ - Id. §11(b)(1).

↩︎ - See, e.g., Wisconsin Stat. § 165.25(6)(a)1; Serv. Emps. Int’l Union v. Vos, 393 Wis. 2d 38, 70-79 (Wis. 2020) (upholding law requiring legislative approval on attorney general litigating for any injunctive relief or conceding the unconstitutionality of any statute, and noting other states, including Arizona, Connecticut, Nebraska, Oklahoma, and Utah, have similar restrictions).

↩︎ - 143 S. Ct. 58 (2022). In Rose, the U.S. Supreme Court reversed a stay granted by the Eleventh Circuit and criticized the appellate court for “appl[ying] a version of the Purcell principle, that respondent could not fairly have advanced himself in light of his previous representations to the district court.” Id. (internal citations omitted).

↩︎ - See, e.g., Susan Tebben, Ohio Secretary of State says redistricting urgent after year of inaction, Oh. Cap. J. (May 5, 2022, 4:55 AM) [https://perma.cc/B3U8-2DUC].

↩︎ - Purcell v. Gonzalez, 549 U.S. 1, 4–5 (2006) (“Court orders affecting elections, especially conflicting orders, can themselves result in voter confusion and consequent incentive to remain away from the polls. As an election draws closer, that risk will increase.”).

↩︎ - Acknowledgements: This report stems from the NRF’s multiyear partnership with the Political Election Empowerment Project (PEEP), a pro bono project at UC Berkeley School of Law. The participants in that project were instrumental to the NRF’s efforts in producing this report, and we are grateful for their work. Thanks also to Christian Grose who has supported this project throughout.

↩︎

The full report is available to download here.

Ensure Every Voice Counts

The National Redistricting Foundation works to advance fair representation, so voters—not political interests—shape our democracy.